Malicious Infrastructure Hunting: Part 1: Core Data Types and The Toolkit

We established the hunter’s proactive mindset in the last post. Now we build the toolkit. You cannot track an adversary without understanding the traces they leave behind. This post defines the data points and the tools required to find them. We will look at the footprints adversaries generate, then build a "go-bag" of free tools to start hunting.

Core Data Types

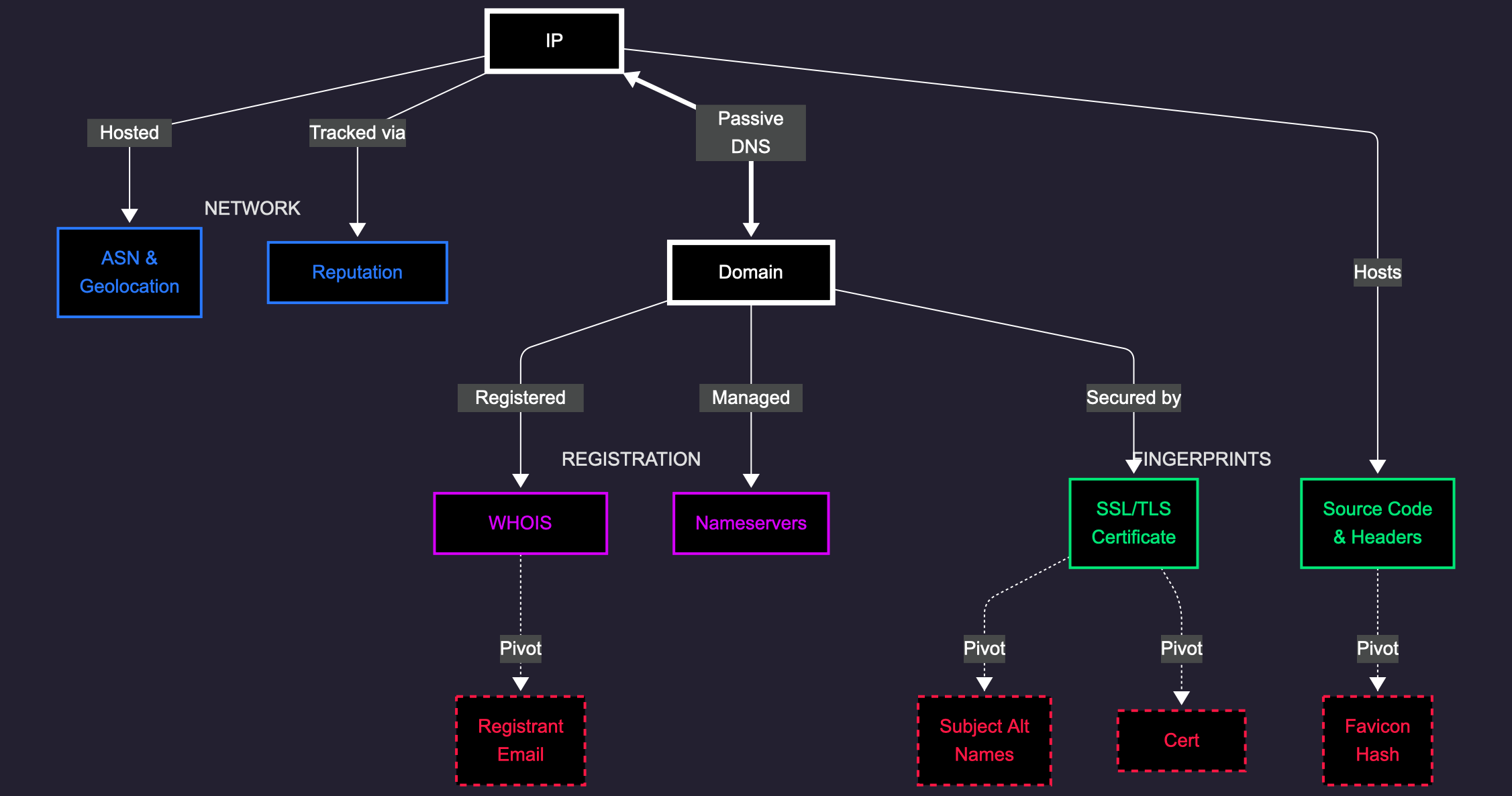

Our investigations relies on connecting distinct data points. A single indicator is rarely enough. You must piece these different data types together to reveal the full scope of a network.

IP Addresses

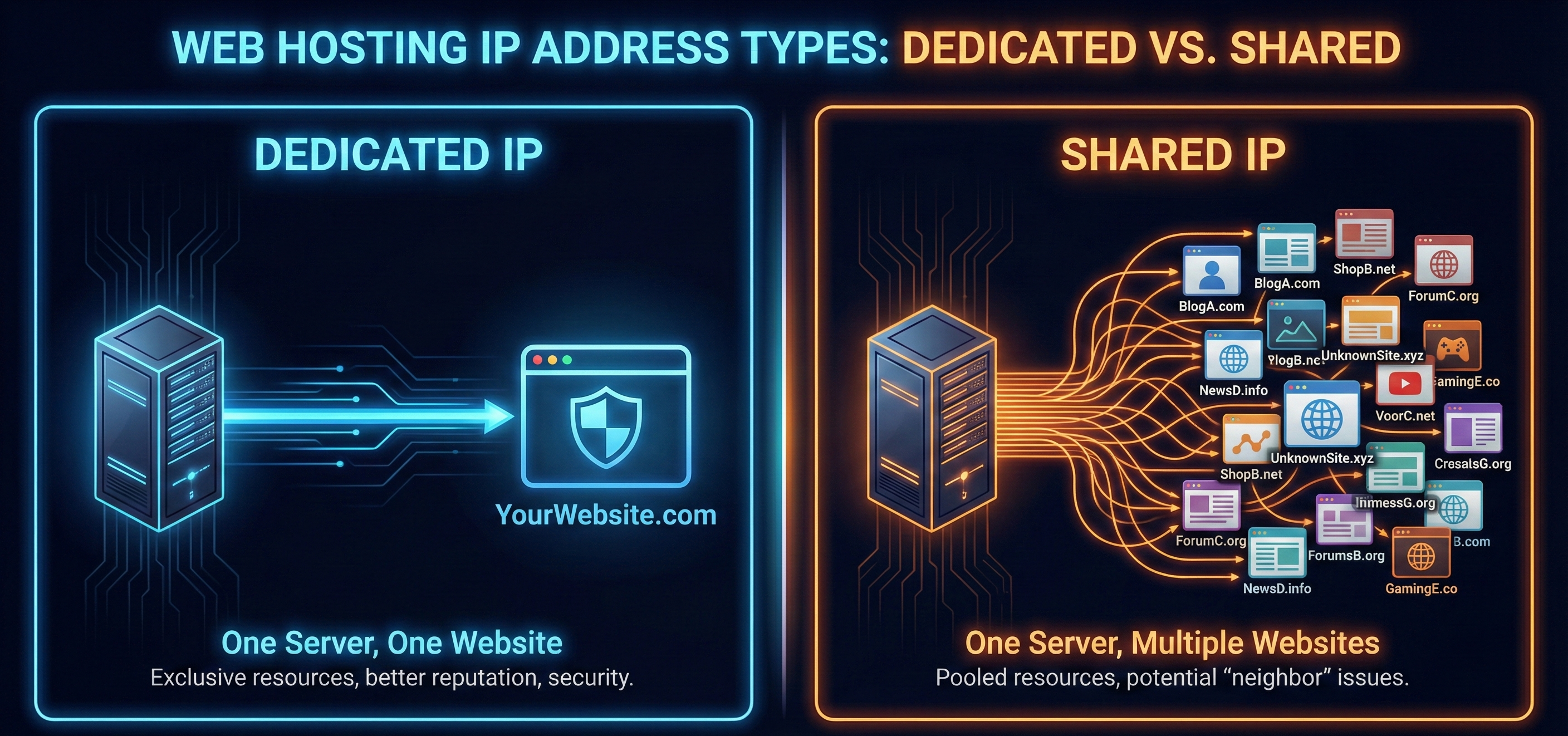

An IP address is a server’s location on the internet, however context is important here.

- Dedicated vs. Shared: This distinction matters most. A dedicated IP hosts a single service. Activity here is directly attributable to one entity. A shared IP hosts multiple unrelated sites. An indicator here is weak evidence. You cannot assume two domains are connected just because they share this IP.

-

ASN and Geolocation: The Autonomous System Number (ASN) identifies the network owner. This reveals where an adversary hosts their infrastructure. Threat actors frequently favor Bulletproof Hosting providers that ignore abuse reports. A recurring presence on these specific ASNs might signal malicious intent.

-

Reputation: Services track IPs linked to spam or malware. This is useful data, but often temporary. Cloud providers recycle IP addresses rapidly; an IP hosting malware today might be assigned to a legitimate business tomorrow.

Domains and Subdomains

-

Registration Tactics: Attackers prefer registrars with lax oversight. They use privacy services to hide ownership details in WHOIS records.

-

Ageing: Newly Registered Domains might trigger security filters. Sophisticated actors register domains and wait months before using them. This bypasses standard Newly Registered Domain (NRD) blocklists.

-

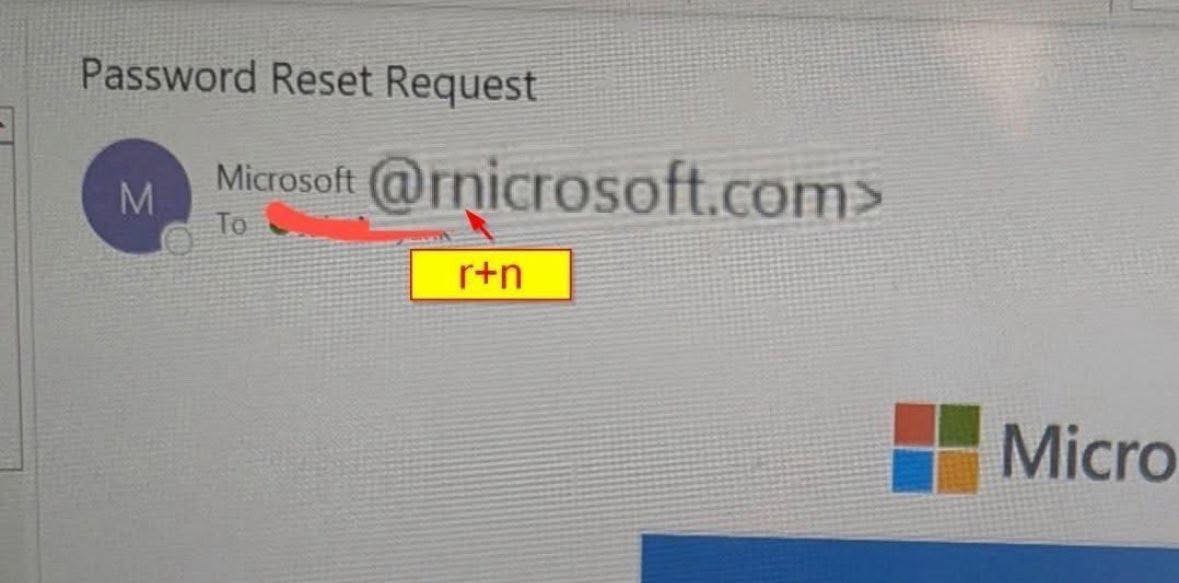

Naming Schemes: Patterns are common.

- Typosquatting: Mimicking brands (e.g.,

micorsoft.com). - Homoglyphs: Using characters that look the same (e.g.,

rnicrosoft.com). - Combosquatting: Adding keywords like login or support to a brand name (e.g.,

microsoft-login.com). - Subdomain Hijacking: Abusing forgotten DNS records pointing to deprovisioned services.

- Typosquatting: Mimicking brands (e.g.,

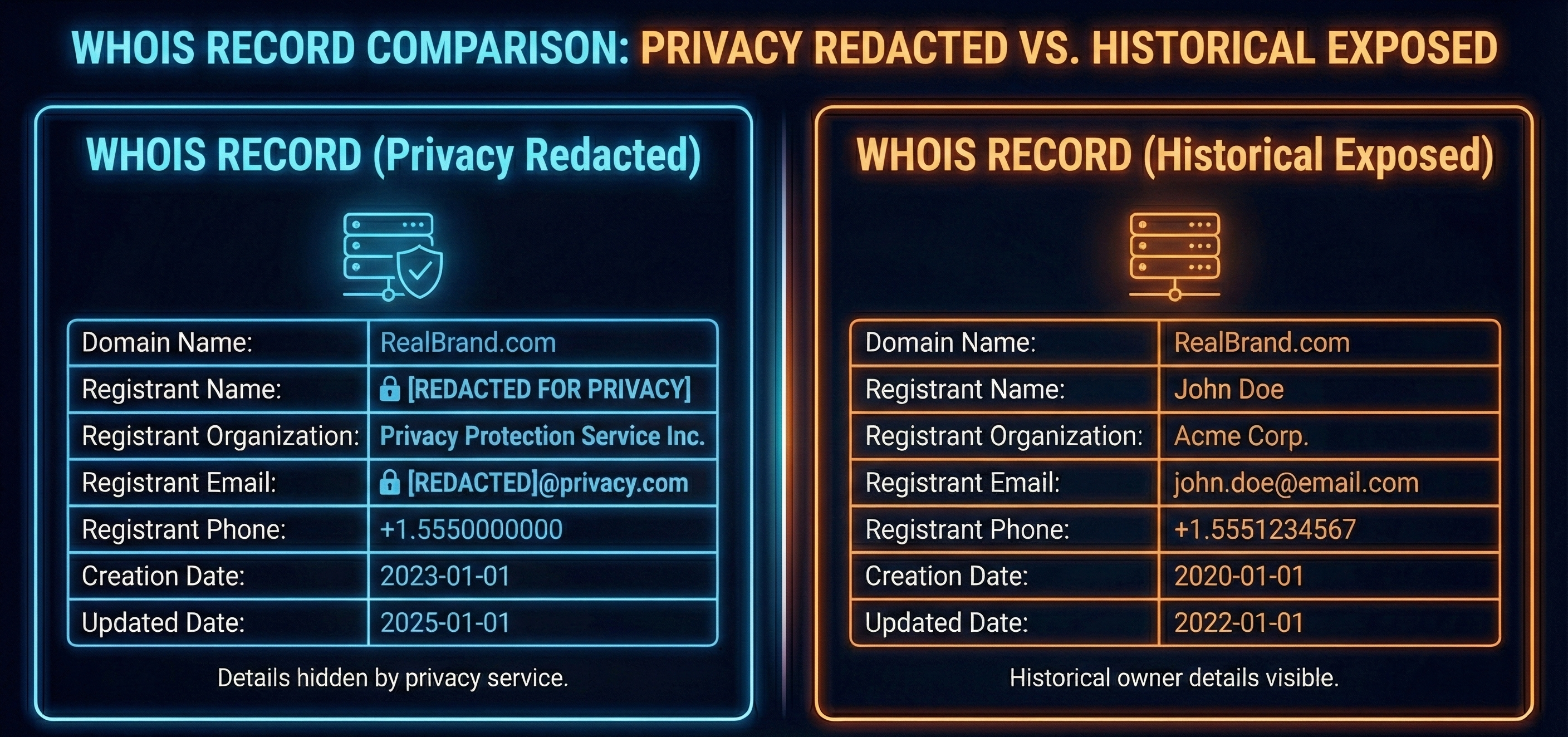

WHOIS Records

WHOIS records ownership history. Privacy guards often hide details, but some clues remain.

-

The Registrar: Attackers often stick to specific providers (e.g., bulletproof hosts or registrars that ignore abuse reports). This creates a weak but useful pivot point.

-

Dates: Bulk registration on a single day indicates a coordinated campaign. A short expiry suggests a short-term "burner" operation.

-

Nameservers: These servers handle DNS lookups. Custom or obscure nameservers linking disparate domains provide a high-confidence signal.

-

History: Historical WHOIS is critical. Attackers make mistakes. A brief exposure of a real email address lasts forever in the archives.

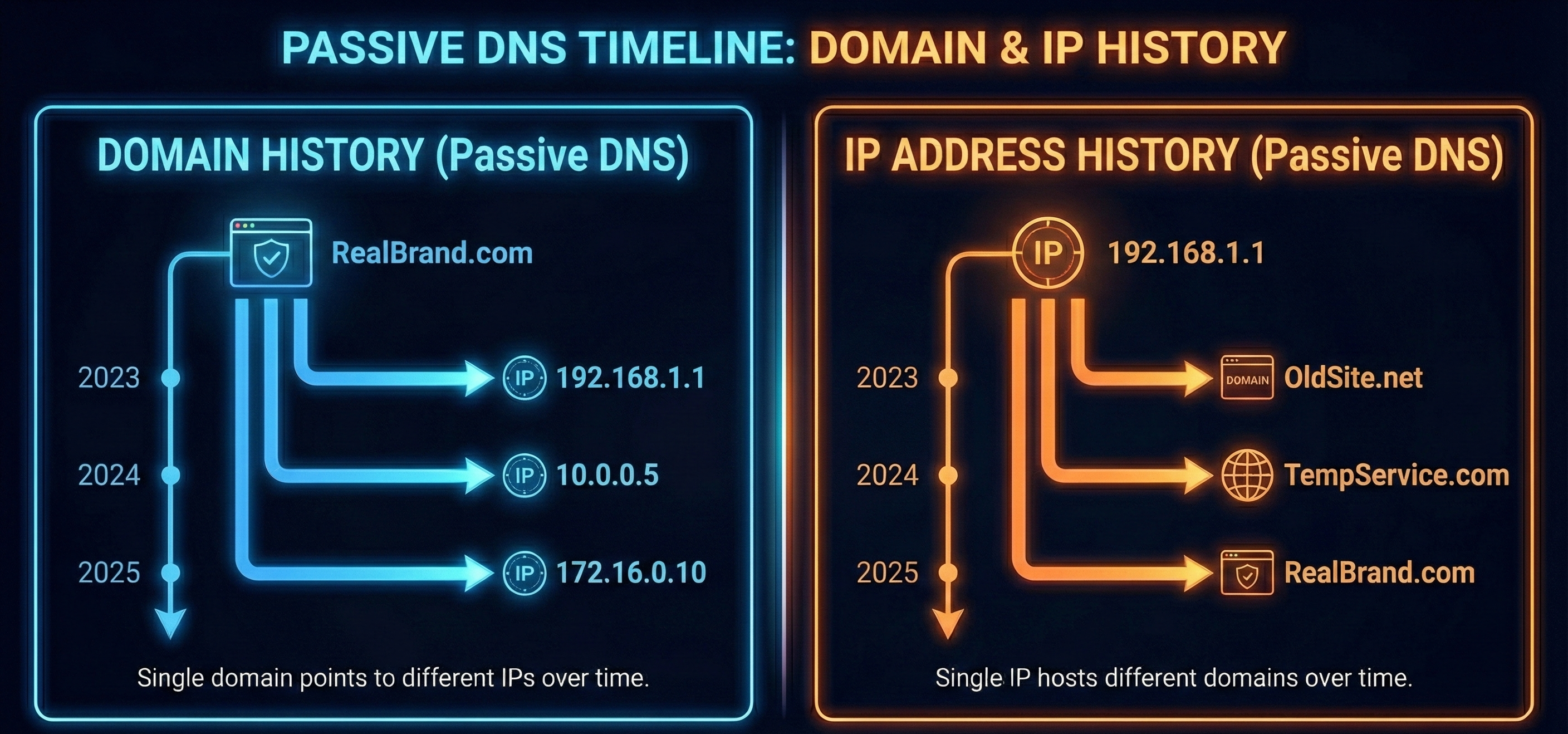

DNS and Passive DNS

Passive DNS (PDNS) logs historical changes. It maps infrastructure over time.

-

Besides A Records:

- MX (Mail Exchange): Shows email handlers. Shared obscure providers suggest a connection (e.g., ten different domains all pointing to the same custom mail server

mail.shady-host.ru). - TXT: Shows verification strings. Matching strings across domains confirm they are owned by the same entity (e.g., multiple domains sharing the exact same

google-site-verificationcode).

- MX (Mail Exchange): Shows email handlers. Shared obscure providers suggest a connection (e.g., ten different domains all pointing to the same custom mail server

-

PDNS Utility: You can trace a domain's IP history to find decommissioned servers. You can also query an IP to see every domain that ever hosted there. This unmasks hidden infrastructure.

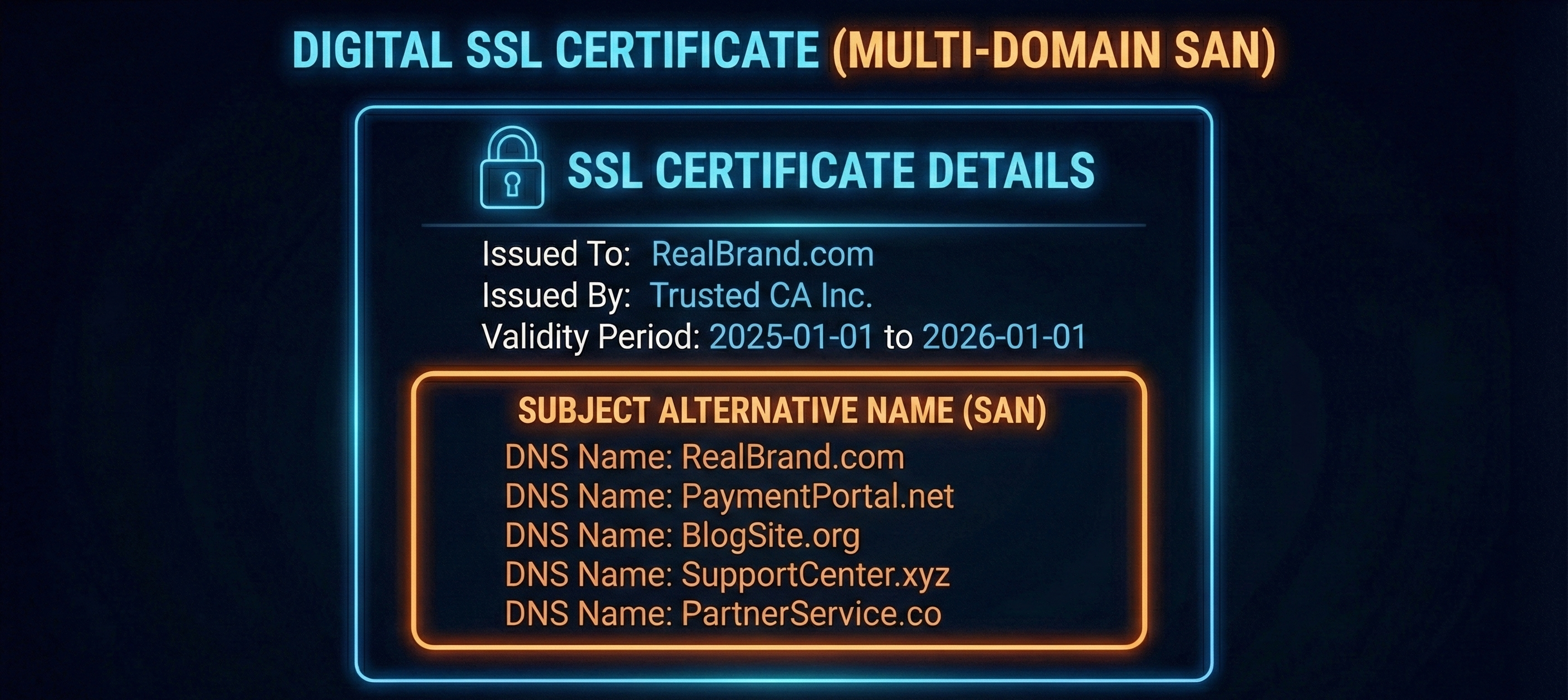

SSL/TLS Certificates

Certificates verify identity. Their distinct attributes track adversaries effectively.

- Subject Alternative Names (SAN): One certificate may be used for multiple domains. This proves the same entity operates all listed sites.

-

Certificate Hashes: These are globally unique fingerprints. Finding the same certificate hash on two different IPs proves they are the same infrastructure.

- Example: Tracking the Cobalt Strike C2 Framework by searching for certificates with the specific Subject Common Name

Major Cobalt Strike, which attackers frequently fail to change.

- Example: Tracking the Cobalt Strike C2 Framework by searching for certificates with the specific Subject Common Name

Web Content and Headers

Servers and kits have quirks. We can use this to our advantage and fingerprint infrastructure.

-

Source Code: Attackers reuse code. Search for specific tracking IDs, comments, or class names.

-

Favicon Hash: Command and Control (C2) frameworks often use default icons. Hash these to find other C2 servers globally.

-

Certificate Hashes: These are globally unique fingerprints. Finding the same certificate hash on different IPs proves they are the same infrastructure. It connects the dots instantly.

- Example: An adversary generates a self-signed certificate for their C2 server. Instead of creating a new one for each node, they re-use the same certificate file for different IPs. Searching for that specific fingerprint exposes their entire network.

The Hunter's Free Toolkit

The industry is flooded with tools. We will focus on a lean, high-quality tools that allows you to cross-correlate indicators effectively without spending any money.

1. The Central Hub: VirusTotal

-

Why it is core: A single search aggregates data from almost every major security vendor instantly.

-

Feature: The "Relations" tab shows connecting infrastructure, including PDNS resolutions and communicating files, allowing you to pivot from one artifact to an entire campaign.

2. Infrastructure Mapping: crt.sh

-

Why it is core: Attackers cannot hide from Certificate Transparency logs. This tool queries them to reveal every subdomain an organization has ever secured.

-

Feature: It exposes hidden infrastructure such as dev.xxx, vpn.xxx, or test.xxx subdomains that standard port scanners miss completely.

3. Visual Analysis: URLScan.io

-

Why it is core: A safe, remote browser that visits dangerous sites for you. It captures screenshots and connection data without exposing your machine.

-

Feature: DOM Capture. It records the page structure and code, allowing you to safely fingerprint a phishing kit even if the visual interface is cloaked.

4. The Time Machine: Wayback Machine

-

Why it is core: Infrastructure dies quickly. The Internet Archive preserves snapshots of domains before they go offline or are cleaned by the adversary.

-

Feature: Visual evidence of past hosting. It confirms if a now-benign domain hosted a phishing template or C2 panel three months ago.

5. Malware Attribution: ThreatFox (Abuse.ch)

-

Why it is core: Reputation lists tell you if something is bad while ThreatFox tells you what the bad thing is. It maps IOCs to specific malware families.

-

Feature: Contextual Attribution. It allows you to pivot from a generic "malicious IP" to a specific threat actor or campaign tag.

Advanced Capability: Internet-Wide Scanning

Bonus: Censys

-

Why it is core: It indexes the internet, cataloguing every service, port, and certificate on a given IP. It reveals the granular technical details of a server.

-

Warning: The free tier is highly restrictive.

-

Strategic Use: Save your limited queries for deep-dive investigations where you need to see specific software versions or certificate chains.

Table 1: The Free Hunting Toolkit

| Tool Name | Primary Use Case | Free Tier Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|

| VirusTotal | Reputation checks and finding connected infrastructure relations. | Advanced pivots and API access are restricted. |

| crt.sh | Instantly discovering subdomains via SSL certificate logs. | None. It is entirely free and open. |

| URLScan.io | Safely visualizing and fingerprinting a live website remotely. | Scans are public by default. |

| Wayback Machine | Viewing historical snapshots of dead or changed websites. | Snapshot frequency varies. Recent sites may be missing. |

| ThreatFox | Attributing indicators to specific malware families. | Focused strictly on malware (no phishing/spam data). |

| Censys | Deep scanning of internet-facing services and certificates. | Heavily restricted. Very few queries allowed per month. |

Conclusion

Tools alone do not stop adversaries. They merely present data. The analyst must interpret that data to find the signal in the noise.

You now possess the foundational knowledge of infrastructure and a lean toolkit to analyse it. Familiarise yourself with VirusTotal, crt.sh, URLScan, and the Wayback Machine.

Part 2 moves from preparation to execution. We will apply this knowledge to real-world scenarios. We will take a single indicator and pivot through these datasets to map an entire threat network.